Talking to GCHQ (interception not required) ...

A remarkable consequence of the Snowden revelations took place last week (14 May), when a former "C" (Chief of the UK's Secret Intelligence Service (MI6)) presided as forty-plus participants from around the world sat down in private for three days to talk intensively through changed approaches to intelligence, security and privacy.

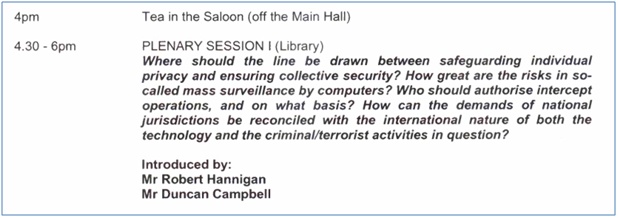

I was asked to open the conference discussions, in conjunction with GCHQ's new Director, Robert Hannigan (pictured below). No-one argued against calls for greater openness. That's a first; coming 40 years after a time when it was a crime in Britain even to mention the existence of GCHQ, and programmes on the subject were banned.

|

|

| The author | Robert Hannigan |

Perhaps to many participants' surprise, there was general agreement across broad divides of opinion that Snowden - love him or hate him - had changed the landscape; and that change towards transparency, or at least "translucency" and providing more information about intelligence activities affecting privacy, was both overdue and necessary. An event like this would have been inconceivable without Snowden.

Away from the foetid heat of political posturing and populist headlines, I heard some unexpected and suprising comments from senior intelligence voices, including that "cold winds of transparency" had arrived and were here to stay.

"We should have seen it coming in the first place", and so put more information in the public domain first, was another observation. (The rules of the conference prohibit attributing any particular remark to any attendee, and also require that contributions are personal and not official positions - although Ditchley normally publishes the names of all participants.)

A different senior speaker reflected that Snowden's actions were an inevitable and perhaps necessary counterbalance to admitted excesses of intelligence collection after 9/11, while also asserting that the disclosures were hugely damaging. You don't get nuanced thoughts like that on Fox News or in Britain's Daily Mail.

Despite the collection of current and former CIA, GCHQ and SIS officials, counter-terrorism commanders, security managers, and former permanent secretaries present, as well as the former chair of Britain's Intelligence and Security Committee, I did not hear the phrase "capability gap" mentioned. That sort of rhetoric seemed to be reserved for the political arena. No-one tried to debate whether Snowden was a villain, traitor or hero.

There was genuine tension between some intelligence demands for personal information from US Internet companies, and the requirements of US law. US regulators and the companies whose officials were present - Apple and Google - could point to the Electronic Communication Privacy Act (ECPA) and to the Fourth Amendment.

The audience and participants at Ditchley Park, a conference centre near Oxford, included intelligence regulators and human rights specialists from Europe and English speaking countries. They were mixed in with twelve current or past directors or senior staff of Five Eyes intelligence and security agencies, including the German BND, France's DGSE, Sweden's sigint agency FRA, Australia's ASIO and ASIS, Canada's CSIS and a former Director and a former Director of Intelligence of the CIA, as well as GCHQ and SIS.

The conference conclusions, which will be published by the Ditchley Foundation shortly, are focussed on possible principles of accountability, regulation and oversight, not allegations of harm.

According to Ditchley's Director Sir John Holmes, he planned the event because "renewed terrorism threats and the Assange and Snowden revelations have put the intelligence debate back in political minds". The purpose of the conference, he said, was to explore "how can governments achieve the right balance between gathering enough information to keep their citizens safe, without those same citizens feeling that their privacy is being unreasonably invaded?"

One of the stipulations made by the intelligence officials and regulators alike at the conference was that there should be "no secret laws" about what agencies do, unavailable to the public. One of those attending, former GCHQ Director and Permanent Secretary Sir David Omand, has written elsewhere that "investigative activity should be regulated by 'black letter law'". Omand's further published suggestion that "not everything that technically can be done should be done" was not disputed.

Curiously, both supervisors and intelligence gathererers appeared to agree that even given the scale of the leaks about NSA and GCHQ activities, "relatively little embarassing information has emerged"; most of what had come out that was embarassing was about spying on friendly states. Other points of agreement were that agencies needed strong external controls, including supervision of internal ethical controls. Oversight should not govern just what was collected, but needed to expand to include the "combination of data" (such as massive metadata analysis), "information sharing", and the "use of intelligence collected". Internet companies should not have to face "ad hoc approaches and conflicts of law". Agencies were asked to use the front door in making requests for law enforcement data, and not (as hitherto) steal it from internal networks by hacking or by intercepting data flows. Unfortunately, Mr Hannigan and his Director of Strategic Policy and External Relation did not stay to hear all of the conference (at least, not in person).

Unhappily, in the big world outside, during the second day of the conference, the UK government was forced to reveal in court that it had just made new and until-then secret (or at least highly obscured) new laws, allowing intelligence and police agencies to hack anyone's computer in the UK without a warrant.

A summary of the discussions at Ditchley is to be published soon. The list of attendees will be included. My colleague Ryan Gallagher has mentioned key names in his report in The Intercept.

The day after the conference ended, GCHQ launched a rainbow-coloured charm offensive to proclaim its "proud" stance against homophobia, bathing the doughnut at the heart of its surveillance operations in the gay pride flag. Their website cites their award from Stonewall as "diversity champions". This is pink-washing, as Glenn Greenwald has commented. I agree - but it is still a welcome change from the 1980-90s when we campaigned against GCHQ throwing out gay staff, and when I was one of the founders of Stonewall. Then, GCHQ were extralegal, unrestrained, unsupervised, unacknowledged, and aggressively unwilling to be open about anything.

I do not know where, if anywhere, the Ditchley conference and the proposed "principles" will lead, beyond an erudite summary of issues.

But we are not in Kansas anymore.